AI accounts for over half the code produced in some organizations, yet 48% of AI-generated code snippets contain vulnerabilities compared to lower rates for human-written code. The industry narrative is clear: AI-generated code is fundamentally less reliable in production.

But what if we’re blaming the wrong thing?

AI-generated code doesn’t come with a self-destruct mechanism. There’s no magical property that makes it spontaneously combust when it encounters a production server. It’s not programmed to self-destruct at 3 AM on a Tuesday, Mission Impossible style.

When Claude writes a Python function, it follows the same syntax rules and runs through the same interpreter as human-written code. The runtime doesn’t check git blame before executing. When AI code fails in production, it fails for the same reasons any code fails: poor logic, inadequate error handling, integration issues, or infrastructure problems. The failure modes are identical.

If AI and human code behave identically at runtime, why do we see that 48% vulnerability rate? The answer reveals something about human behavior, not code behavior.

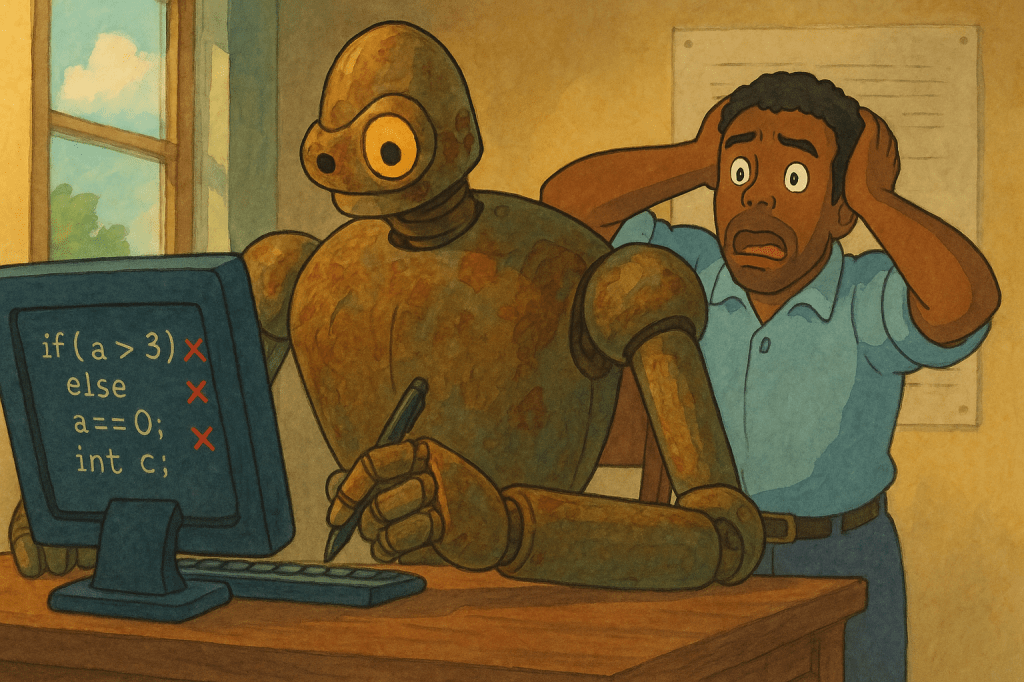

Here’s what actually happens: developers treat AI-generated code differently during development. When we write code ourselves, we naturally add error handling because we’ve been burned before. We test edge cases because we remember when things broke. We review carefully because we know our limitations.

With AI code, something shifts. It looks polished and complete, so we treat it as more finished than it actually is. We’re less likely to test thoroughly, review critically, or add defensive programming. The higher vulnerability rate isn’t because AI writes worse code — it’s because we apply less rigorous development processes to code we didn’t write ourselves.

The Process Reality

During my first internship week in France, I nearly wiped out an entire production database with a poorly written SQL Server stored procedure. The only thing that saved the company’s data was my supervisor’s wisdom in giving me access to a separate database environment because he knew junior engineers mess up and write bad code. Regularly.

This wasn’t mysterious AI unpredictability — it was a classic case of inexperience, insufficient testing, and inadequate code review. The stored procedure I wrote had a logic flaw that could have cascaded through the entire database. No language model was involved — just a human developer who didn’t fully understand the implications of the SQL they were writing.

Knight Capital lost $440 million in 45 minutes because of a human coding error that deployed the wrong algorithm. (Fortunately for me, I only had to buy the whole team breakfast when my stored procedure failed.) These were engineering process failures, not inherent code reliability issues. The same process failures happen with AI code, but more systematically.

There’s another important factor: hastily written code will eventually fail in testing just as it fails in production, given enough time and the right conditions. What appears to be “AI code failing in production” is often just bad code revealing itself under specific conditions that weren’t explored during testing.

A poorly written function will crash when it encounters null values, regardless of authorship. A database query without proper error handling will timeout under load. An API integration without retry logic will fail during network issues. Similarly, misunderstood code will fail if you don’t fully grasp its purpose — it might be doing something entirely different than what you intended, whether you copied it from Stack Overflow or generated it with an AI tool. These failures aren’t production-specific — they’re condition-specific.

If your testing process had encountered the same edge cases, input combinations, or load patterns that triggered the production failure, the code would have failed in your staging environment first. The failure happened in production because that’s where those particular circumstances first occurred, not because the code was inherently unreliable.

AI‘s actual problems

AI does have genuine weaknesses that developers need to understand and account for:

Over-engineering and Excessive Fallbacks: AI often generates unnecessarily complex code with excessive error handling and defensive programming. It might add try-catch blocks for every possible exception, create multiple fallback mechanisms, or implement overly cautious validation that makes the code harder to read and maintain. Claude 3.7 Sonnet was particularly notorious for this — creating solutions that looked robust but were actually over-engineered for simple problems. To recognise these, you need to know what you’re looking at.

Knowledge and Context Limitations: AI code is often outdated due to knowledge cutoff points in language models and the rapidly evolving nature of programming frameworks. A model trained on data from early 2024 might suggest deprecated APIs or miss recently introduced best practices. AI also can’t see your entire codebase, so it suggests code that may be inconsistent with existing patterns, naming conventions, or architectural decisions.

Security and Supervision Gaps: AI needs strict human supervision and won’t consider security vulnerabilities, performance implications, or practical concerns without explicit prompting. When asked for a solution, AI delivers functional code but rarely includes comprehensive error handling, logging, or graceful degradation. Human developers bring unconscious domain knowledge, contextual awareness, and implicit security concerns that AI models simply don’t possess.

Scale and Integration Issues: AI is weak at coding complete applications — you can’t reliably “vibe code” a full video game or complex system. The output becomes incoherent at scale and lacks proper architecture. AI also occasionally suggests functions, methods, or libraries that don’t exist, particularly for less common frameworks, and struggles with complex business logic that requires deep domain understanding. Additionally, AI-generated code often uses different coding styles or architectural approaches than your existing codebase, creating maintenance headaches over time.

However, for individual functions, utility scripts, and isolated components, AI can produce genuinely useful starting points. The key is understanding these limitations and treating AI as sophisticated autocomplete for experienced developers, not as a replacement for engineering judgment.

The next time “AI code fails in production,” ask different questions: Was it tested as thoroughly as human-written code? Did it get proper code review? Were edge cases considered?

Most AI code failures trace back to the same engineering fundamentals we’ve always dealt with: insufficient testing, inadequate review, poor integration practices. But understanding AI’s specific weaknesses lets us be more systematic about addressing them:

For AI’s over-engineering tendency: Review generated code for unnecessary complexity. Ask “Can this be simpler?” before deploying.

For context gaps: Always check that AI-generated code matches your existing patterns, naming conventions, and architectural decisions. Don’t let AI dictate your codebase style.

For security blind spots: Treat AI code like junior developer code — assume security considerations are missing and review accordingly. Never deploy AI-generated code without explicit security review.

For outdated knowledge: When AI suggests APIs or libraries, verify they’re current and still recommended. A quick documentation check can save hours of debugging deprecated methods.

For integration issues: Test AI code more thoroughly at system boundaries. AI doesn’t understand your specific integration requirements, so failures often happen at the edges.

The solution isn’t avoiding AI tools — it’s being intentional about where we apply extra scrutiny. Treat AI as a productive junior developer: capable of good work, but requiring experienced oversight in predictable areas.

AI doesn’t change the rules of reliable software, but it does require us to be more explicit about applying them. The problem isn’t AI code — it’s assuming AI code needs less scrutiny than our own.

Leave a comment