I’ve spent the past few weeks building data pipelines and machine learning models. Not for work—for the Los Angeles Rams. On weekends. For free.

This probably needs some context. I build AI agents, wrangle data, and occasionally argue with LLMs about what year it is—because I’m paid to, and because I genuinely enjoy it. But I also have a habit of applying those same skills to things nobody asked for. Most engineers have side projects. Usually it’s a half-finished app or yet another to-do list. Mine is a collection of machine learning models designed to predict which college prospects the Los Angeles Rams should draft.

Why the Draft?

I got into the NFL about eight years ago, mostly by accident. ESPN highlights, YouTube breakdowns, the TV show Ballers—it pulled me in, and at some point I became a genuine football obsessive. A Rams fan, specifically, despite half my cousins living in Boston and bleeding Patriots blue. I watch everything now. Regular season, playoffs, Combine, Super Bowl, even the Pro Bowl. But the Draft is the one that got me building things.

If you’re not familiar with the NFL Draft, it’s essentially a three-day event where teams take turns selecting college players. But that undersells it. The Draft is an industry within an industry. In the months leading up to it, there’s a parallel economy of mock drafts, scouting reports, pro day workouts, Combine measurements, leaked intel, and endless speculation. Entire media careers are built on predicting who goes where. And behind the scenes, billion-dollar organizations are making decisions that will define their franchises for years—sometimes based on a tenth of a second in the 40-yard dash, sometimes based on a gut feeling from a scout who watched a kid play in the rain.

What fascinates me is how opaque those decisions are. A team passes on a prospect everyone expected them to take. Another team reaches for a guy no one’s heard of. The internet melts down. And then three years later, that “reach” is a Pro Bowler and the “steal” is out of the league.

I wanted to understand what’s actually happening. Not the narratives, not the hot takes—the patterns. What makes front offices tick? What do the Rams, specifically, look for when they’re spending draft capital on a player? Could I reverse-engineer their preferences from 12 years of data?

So I went at it.

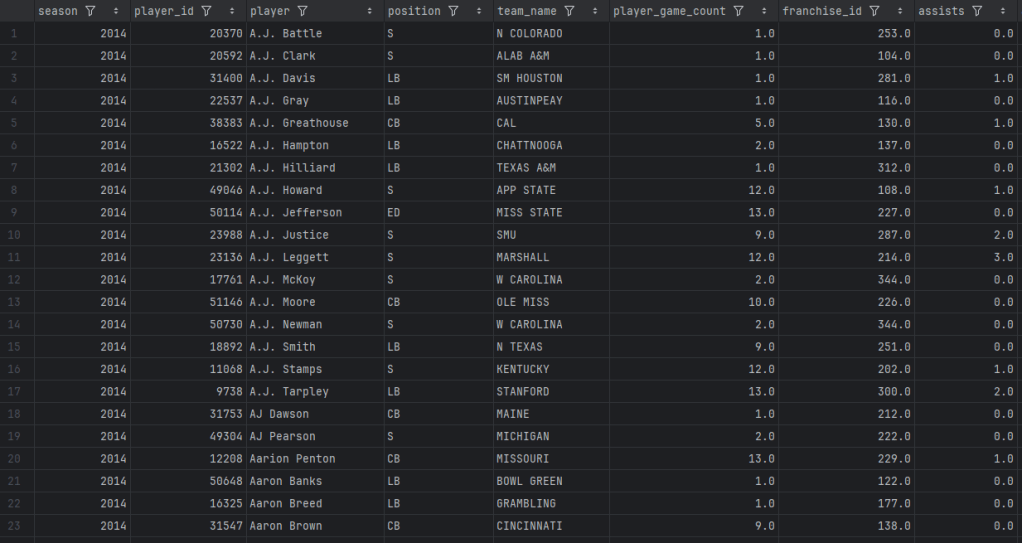

The Data Pipeline

I wrote a Playwright scraper to pull Combine measurements for over 6,000 players—40 times, verticals, broad jumps, the works. This was my first time since my master studies doing web scraping (shout out Professor Fernandes who gave me an excellent grade for that project). I exported PFF college stats going back to 2014, tracking everything from coverage grades to route running scores to yards after catch. I pulled SP+ ratings from CollegeFootballData.com to adjust for strength of schedule, because level of competition really matters at the collegiate level where future professional athletes might be playing against future accountants and computer scientists.

Three Projects, Three Approaches

Each project pushed me to try a different statistical approach, depending on what the data demanded.

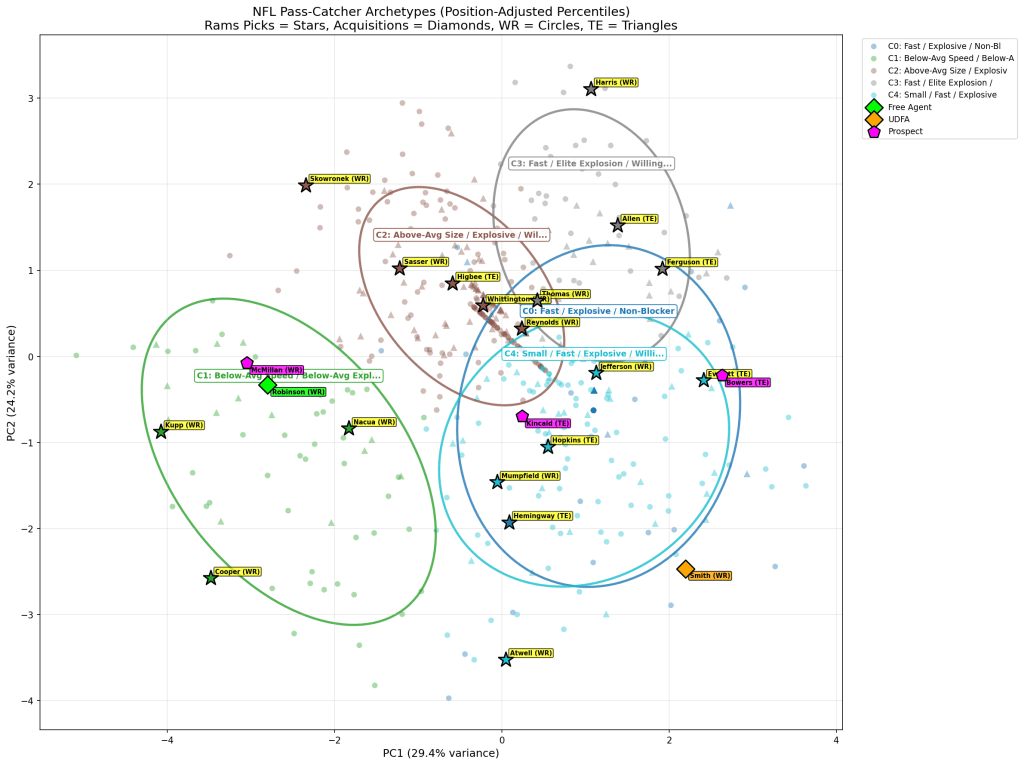

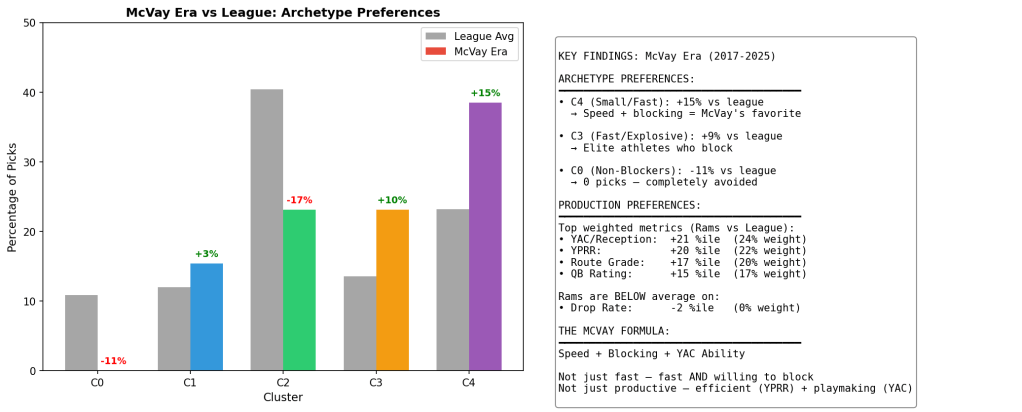

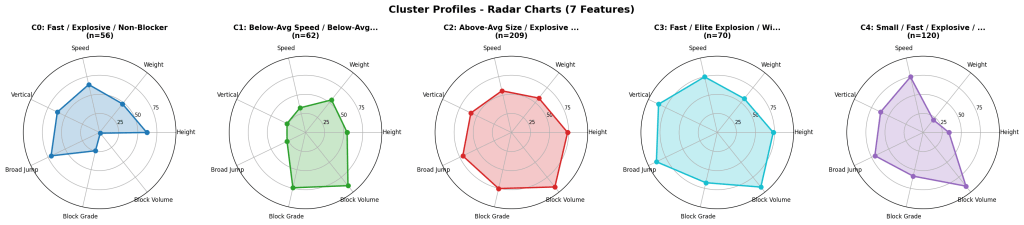

Wide Receivers: Clustering for Archetypes

For receivers, I used K-means clustering to group players into athletic archetypes. The interesting finding: the Rams’ best picks don’t cluster with the athletic freaks. They cluster with the technicians who block. That tells you something about scheme fit that raw athleticism scores miss entirely. I actually did a 3D cluster chart for the first time ever (see below).

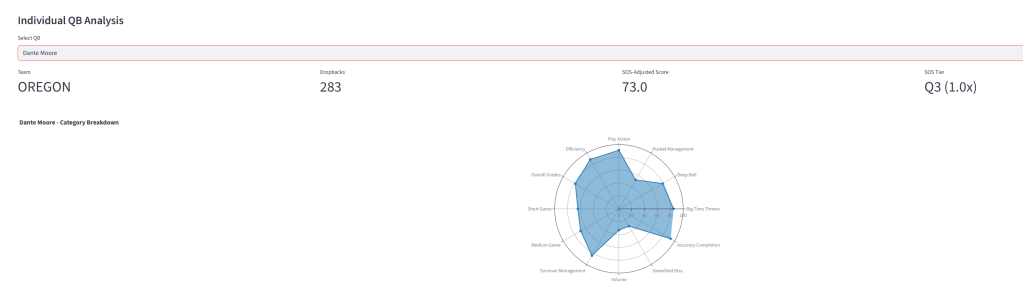

Quarterbacks: Weighted Composite Scoring

The quarterback project forced me to think about how to weight categories against each other. I built a percentile-based composite scoring system covering 59 PFF metrics across 12 categories—big time throws, deep ball accuracy, pocket management, play action efficiency. The goal was to create a “Stafford Profile” and measure how closely prospects match it.

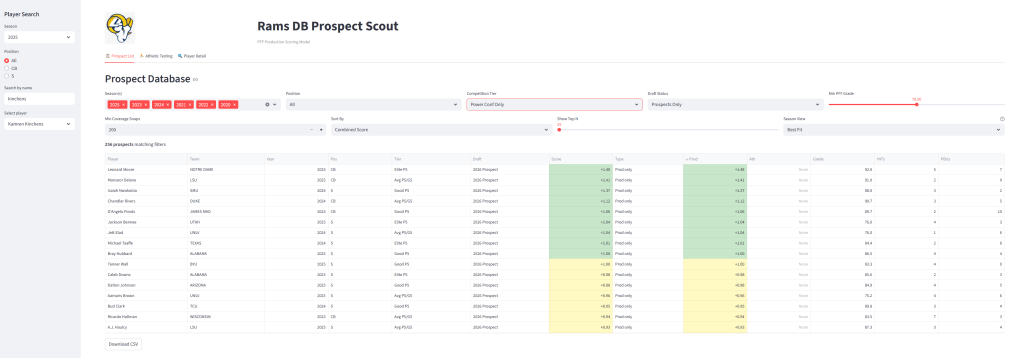

Defensive Backs: Small Sample Rigor

The defensive back project was my most statistically rigorous—because it had to be. With only 16 cornerbacks and 13 safeties in my Rams draft history dataset, I couldn’t afford to chase noise.

I ran one-sample t-tests on 100+ metrics to determine which preferences were statistically significant versus random variation. Metrics that passed got weighted by Cohen’s d (effect size). For player comparisons, I used cosine similarity on rate-based metrics—interceptions per target instead of raw INTs—so that lockdown corners who don’t get targeted still match correctly.

The result: a weighted scoring model where production counts for 70% and athleticism for 30%, derived from validating against every DB the Rams have acquired since 2012.

What the Models Actually Found

Here’s where things got interesting. The statistical analysis revealed preferences I didn’t expect.

The Rams love man coverage specialists. Their cornerbacks average 1.2 interceptions in man coverage per season—versus 0.2 for the league average. That’s 6x the production. The z-score on man coverage INTs was +1.88, the strongest signal in the entire dataset.

Size doesn’t matter. I assumed there’d be a physical archetype. There isn’t. The Rams have acquired corners ranging from 5’9″ Cobie Durant to 6’3″ Ahkello Witherspoon to 166-pound Emmanuel Forbes. Production and traits trump measurables.

Speed is overrated—agility isn’t. For corners, 3-cone drill and vertical leap are weighted 2.2x higher than 40-yard dash. The Rams can overlook pedestrian straight-line speed if you test well in change-of-direction.

When I validated the model retrospectively, it correctly identified players like Durant, Trevius Hodges-Tomlinson, and Witherspoon as strong scheme fits before they were acquired. The most telling example: Kamren Kinchens ran a 4.85 40 at the Combine (historically slow for a safety) but posted a 90.7 coverage grade in college. The model flagged him as a fit despite the speed concerns. He’s now one of PFF’s highest-graded safeties in 2025.

What’s Next

The 2026 Combine hasn’t happened yet, so right now I’m working with production scores only. Once the athletic testing drops, I’ll plug in the numbers and see what shakes out. There’s something satisfying about watching a dashboard populate with fresh data—prospects shuffling up and down the rankings, new names appearing that weren’t on my radar before.

I post the results on Rams forums sometimes. Methodology breakdowns, prospect rankings, the occasional deep dive on a player nobody’s talking about. People seem to enjoy it—there’s a good community of fans who actually want to dig into the numbers rather than just react to mock drafts. Someone will ask “what about this guy from Toledo?” and I’ll go run him through the model just to see what comes out.

I’ve learned a lot about applied statistics from these projects—practical problems have a way of making concepts stick. But mostly, it’s just satisfying to build things around something you actually care about.

I’ll publish my 2026 board once the Combine numbers are in. If you want to argue about whether the Rams should take a corner or a receiver in round two, or just talk some football, you know where to find me!